Bosnia: The Meeting of Cultures

Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia is representative of Bosnia as a whole - the 'meeting of cultures', where East meets West. The touch of the two main historic periods and empires that molded the city: the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian are evident in the buildings, food, places of worship and music.

Photos: Baščaršija, Sarajevo (below left), Sanski Most (below centre) Bosnian coffee (below right)

Sexual Violence in Conflict

Bakira's Story

It is estimated that up to 50,000, mainly Muslim women, suffered extreme sexual violence during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many of the women were systematically and repeatedly raped by Bosnian Serb soldiers and paramilitaries. It was used as a cheap, but effective and devastating weapon of war. They were then forced to carry their babies to full-term “to dilute their Muslim blood.”

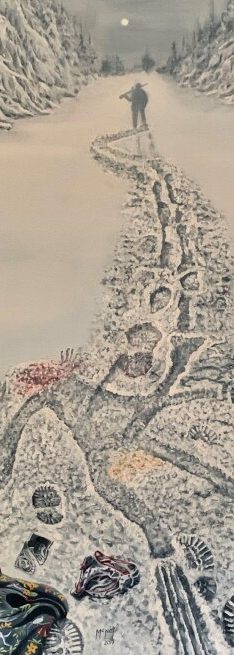

This painting highlights the silence surrounding these violent crimes that soldiers felt they could commit with impunity. The snow, and therefore the evidence will soon be gone, but not the night-terrors and mental health issues that may never fade for the victims. The tangled forest represents escape was impossible.

Bakira Hasečić’s story inspired the painting of this picture. In 1992, the local police chief, along with Bosnian Serb soldiers entered her home. They placed the family under house arrest, repeatedly raped Bakira and her eldest daughter and robbed them of their savings. The soldiers then slashed her daughter’s face and they were left for dead.

Bakira, despite constant threats, has dedicated her life to the Association of Women Victims of War to help bring the perpetrators of war-rape in Bosnia and Herzegovina to justice and to support other victims.

Her attackers have never been arrested.

Child Survivor Testimony

Melisa Mujkanović

My mother bought this jacket for me from a boutique shop in Bosnia. This is what I was wearing when I left our house for the last time, before it was destroyed by Serbian forces, and what I wore throughout our occupation during the genocide. This jacket has witnessed countless atrocities - some of which I speak of, most of which I don’t - much like most genocide survivors.

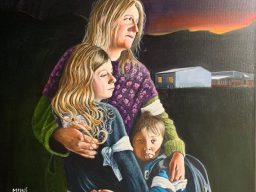

My mother, sister and I were separated from my father and were detained in the Trnopolje concentration camp. My father survived the Omarska, Keraterm and Trnopolje concentration camps and we were reunited with him a year later in England, upon discovering that he was alive when he appeared on the news.

During our occupation in the Trnopolje concentration camp, we slept on concrete, outside, huddled in the corner of a school classroom, with nothing to eat and little to no water. We drank rain water to survive; that in itself is a blessing.

My mother protected me and my sister under the weight of her own body from continuous shelling above us, cut our hair so that we looked like boys, squeezed us into the corners of rooms and covered us with discarded clothes that she had found, in order to protect us from Serbian guards who were perpetually raping women and young girls.

Serbian guards forced us into carriages for livestock, with the numbers of women and children always decreasing as they raped them and disposed of their bodies. In Paklenca, after commanding us to line up at the edge of the River of Bosna, Serbian guards pointed their rifles at us and threatened to shoot us into the river.

But Bosnians are like grass: when the hay carts pass over the grass and the wheels move on, every blade rights itself again.

Robert McNeil Collection

Where are the Children

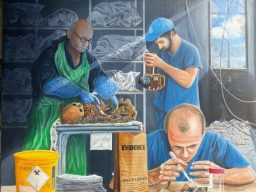

Whilst checking a shoe removed from the body of a male Muslim victim of genocide that was found in a mass grave near Tuzla, Bosnia in 1996, I found a small faded photograph of a young boy, aged about 6 and a girl aged about 10, hidden under the insole of his shoe. Two women, possibly their mother and grandmother were standing beside the children. Apart from this treasured photo there was a personalised prayer to the victim, presumably written by the imam from his village, on a screwed up piece of paper. There were no other possessions found on the victim. He died after being shot in the head. His hands were bound together with wire. We wondered what happened to the women and children. Both the photo and the prayer helped identify the victim. As well as whole bodies, many hundreds of separate body parts were discovered in ‘secondary’ graves. The primary graves had been exhumed by the Serbs and buried in new graves in an attempt to conceal or disrupt the evidence. Many of those body parts, through time, were reconstructed and eventually returned to the families for respectful burial. This painting represents to me both the human and de-humanising aspects of the horror of war.

For more of Robert McNeil's artwork click learn more

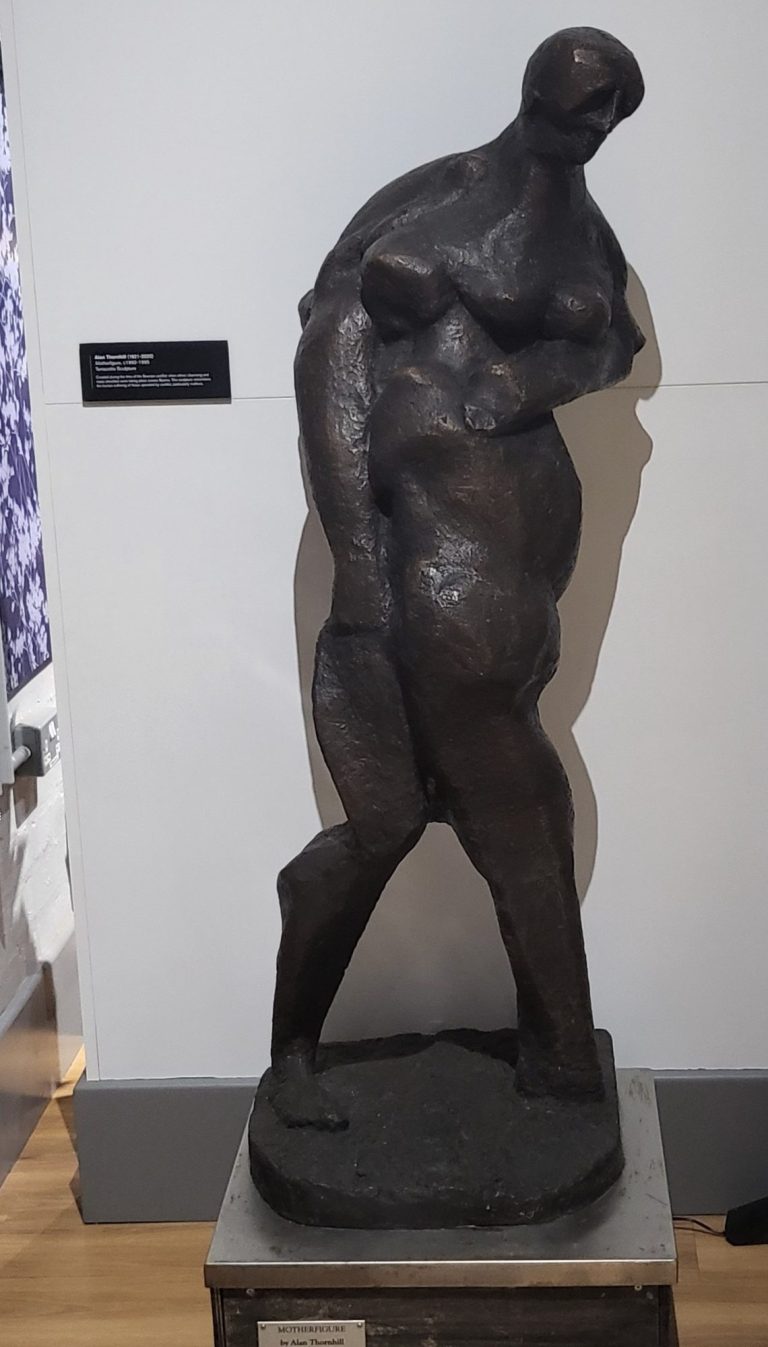

Grave Embrace

Torn rags of clothing, rifle bullet shell casings, personal belongings, scattered and broken bones, the remains of innocent men women and children, together with the stomach-churning odour of death, make up the scenes of carnage in the mass graves.

The forensic experts carefully removed them from this hell, cleaned and put them together again, identified the bodies and returned them to their families to allow some form of dignity in death, and giving them the opportunity to grieve.

This painting is in recognition of those experts, and in memory of those who died needlessly.

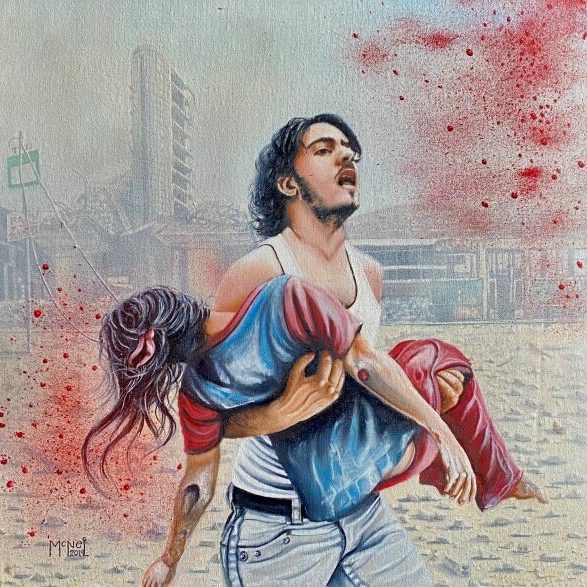

Lens Flare

The subject of this painting was inspired by the death of journalist and war correspondent Marie Colvin who was killed while covering the siege of Homs, Syria in February 2012. I transferred the background to the siege of Sarajevo, as I believed there were strong parallels between the conflict in Syria and the Bosnian War.

In this painting, I wanted to demonstrate not only the needless killing of the innocent but also represent the dangers facing those who record and report from such war zones.

The title refers to the blood-spattered camera lens of the photographer. In the background is the newspaper building Oslobođenje, where despite being shelled every day by Bosnian Serb snipers, cannons, mortar, and tanks, journalists managed to produce a daily news-sheet.

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.